How to Decide What is Necessary

Recently, I made the decision to convert my site from a Single Page Application (SPA) to a Full Stack Application (FSA) due to limitations I encountered around SEO and social sharing. It was a tough decision, but ultimately, I needed to make a change to achieve my desired results. Once the decision was made, the next challenge was determining what steps were necessary to make this conversion happen.

Having worked in the tech industry for nearly a decade, I am well-versed in the Agile methodology. One of the most influential books I've read on planning and executing projects quickly and effectively is "Shape Up" by Ryan Singer from Basecamp. In this book, Ryan discusses the process of breaking down ideas into smaller pieces and determining what is necessary for project success. He refers to this as making the right bets.

As I began contemplating the conversion of my site, I considered what I already had in the form of the SPA, what improvements were needed, and what future capabilities I wanted to incorporate. Looking ahead was crucial to ensure I didn't limit myself in the future, as I had done with the initial decision to create a Single Page Application.

Ideation Process

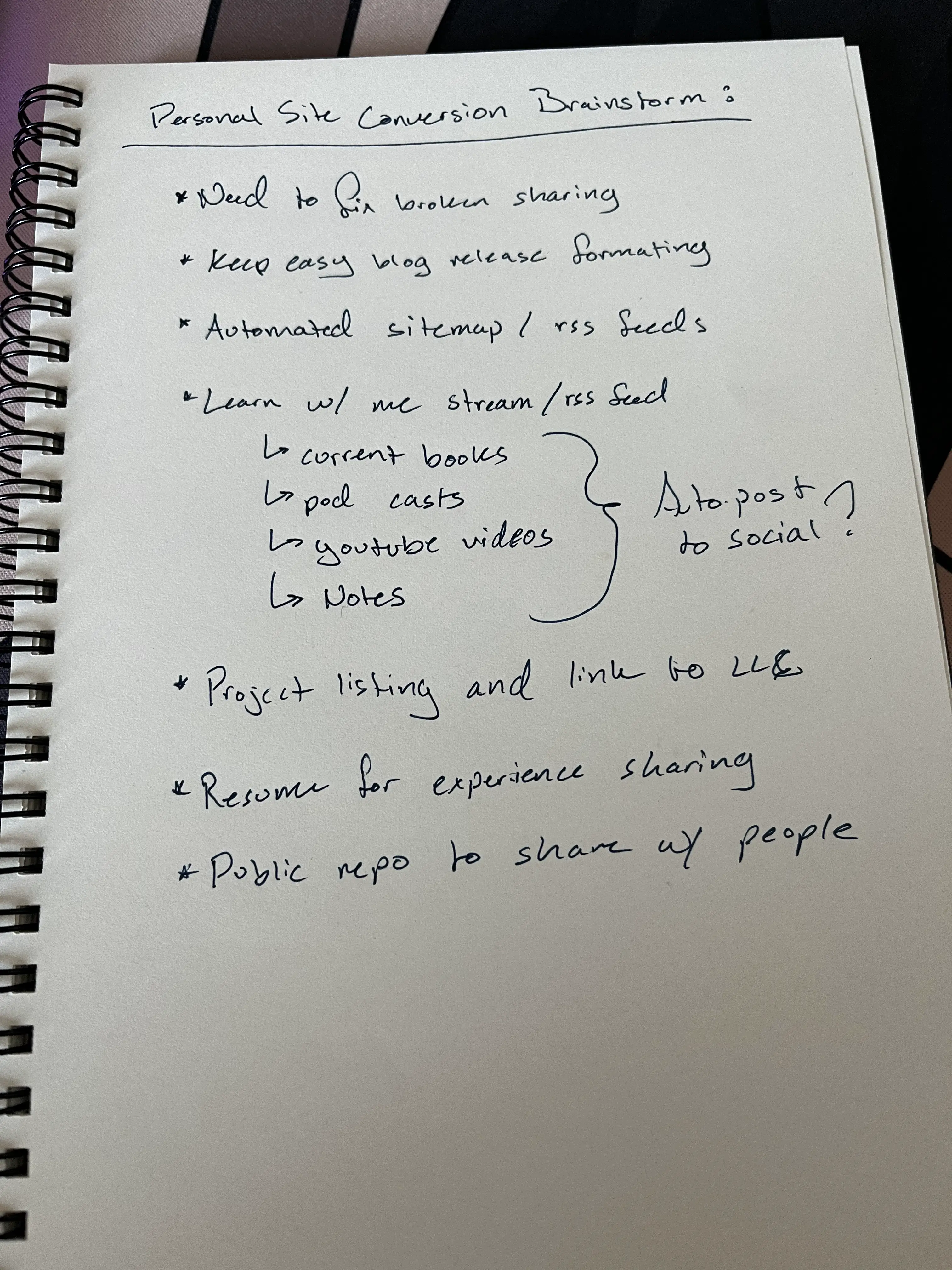

When approaching a project, I always start with brainstorming. This initial input is often vague but incredibly valuable. In this case, the directive was to convert my site to a more flexible and SEO-friendly framework. I began by considering what I needed from my personal site, its purpose, my expectations, and the features/functionality required to achieve them.

Brainstorming can be a lengthy process, so I typically time-box it to 30 minutes to an hour. During this time, no idea is rejected. This approach stems from my experience working with Kevin O'Connor at FindTheBest, where he enforced the "No bad ideas in brainstorming" rule to ensure all ideas were considered before making decisions.

I jotted down all the things I wanted to fix, accomplish, and improve, without diving into implementation details. These notes represented a list of ideas rather than requirements or implementation specifics. Detailed planning would come later; for now, I needed clarity on what I wanted to achieve.

With these notes, I successfully transitioned from the abstract directive of "convert my site to a Full Stack Application" to a list of bugs and features I wanted to address. Now it was time to start making decisions.

Choosing the Stack

The first decision I needed to make was selecting the stack to use. After spending time transforming the abstract directive into a concrete list of features, I had a better understanding of my desired direction and could evaluate the available options more effectively.

Let's use something I'm familiar with

When choosing a stack, familiarity with the tools we use allows us to work faster. Therefore, I wanted to use something I was already familiar with. This narrowed down the list of frameworks to two options:

- Ruby on Rails

- Next.js

Considering my experience, Rails was the more tried and true option compared to Next.js. Consequently, I quickly decided to use Ruby on Rails.

Do I need a database?

The original design of my site was static, so no database was required. This simplicity had its advantages, as managing databases can be challenging and costly. However, I evaluated my future goals for the site, the functionality and features I wanted to provide, and realized that I would need a database to achieve them. Therefore, the decision was made to incorporate a database.

How can we keep deployment simple?

Simplifying the deployment process is crucial. The more automation and streamlining involved, the fewer maintenance headaches and more time available for building features and content. This ruled out self-hosting using Linode or AWS EC2, as well as databases on those systems due to their high costs.

Once again, I relied on my tried and true approach: a Heroku dyno with a free Postgres database through SchemaToGo, and a Cloudfront distribution for caching and rate limiting. Leveraging some of the existing infrastructure from the Single Page Application decision was also possible. All of this was to be automated through Terraform.

Final Stack List

- Ruby on Rails

- TailwindCSS

- Terraform

- Postgres Database

- Heroku Dyno

- Cloudfront Distribution

- AWS Route53 for DNS

Now that I knew the "what" and the "how," I could start prioritizing the work.

Setting Priorities

With the chosen stack in mind, and since it was something I was already familiar with, I could begin prioritizing the tasks. I grouped them into three distinct categories:

1) Feature Parity: Items necessary to have a 1-to-1 replica of my personal site running on the new stack. 2) Bug Fixes: Items necessary to fix for a stable and reliable site, as well as any deficiencies in the current site that necessitated the conversion. 3) Enhancements: Items that would be nice to have but not essential for considering the conversion a success.

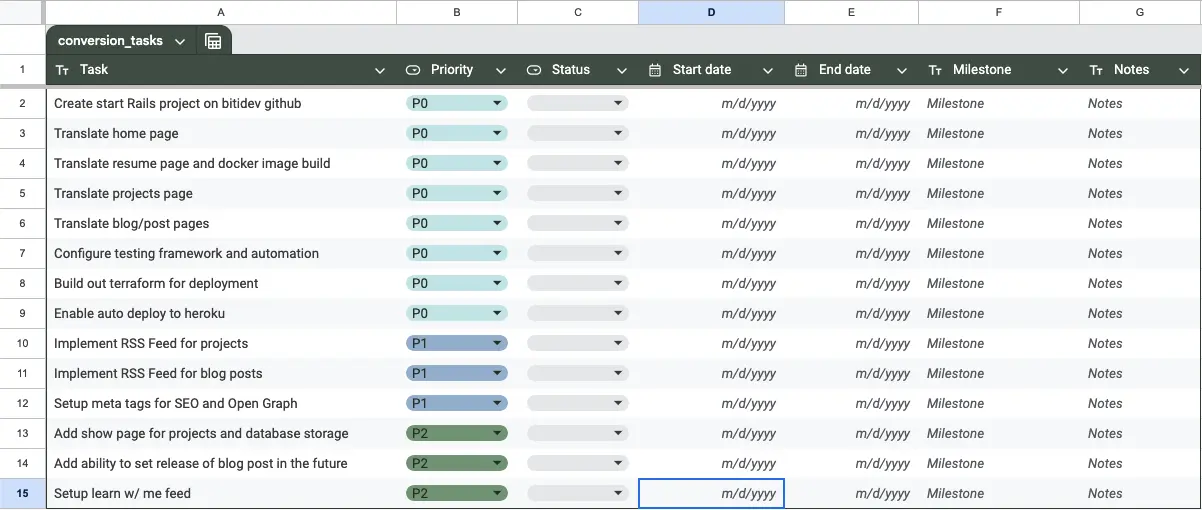

While categorizing, I also considered breaking down larger items into smaller, deliverable chunks of work. This approach allows for better prioritization and helps trim the project's scope to a manageable size, or even more importantly, something that can be completed over a weekend. As seen in the spreadsheet below, the list expanded from 7 line items to 14, providing more clarity on the tasks at hand.

Now that I knew my priorities, I could start building. However, before diving in, there was one more step: trimming the list. I needed to decide what was necessary, what were stretch goals, and what were push goals.

Defining Success

With these three categories, there is an intuitive order, but prioritization also requires defining what "done" looks like. Where do we draw the line in the prioritization list to consider the current initiative complete, allowing us to shift focus elsewhere?

One cornerstone of the Agile methodology is the concept of a sprint, a time-boxed period where the team focuses on a set of priorities and delivers a tangible outcome at the end. I found this concept incredibly useful for determining what was necessary, what were stretch goals, and what were push goals.

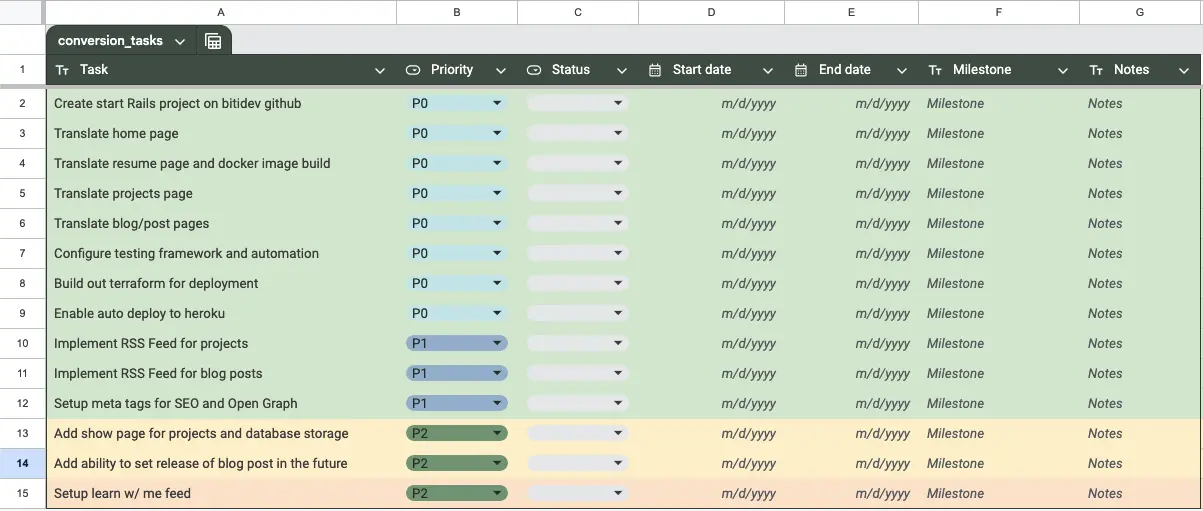

For this initiative, I aimed to complete the entire process within a weekend. Therefore, I set my sprint time-box to two days and reevaluated the spreadsheet to determine what I could realistically accomplish within that timeframe. The result was as follows:

Green items were 100% necessary for considering the conversion a success, yellow items were nice to have, and orange items were push goals for future iterations of the site. With this ordered and prioritized list, I knew when I had reached success. The only thing left to do was to build and iterate.

Building and Iterating

With the chosen stack, established priorities, and a clear definition of done, I could begin building. However, as I progressed, I would constantly iterate on the priorities. Building would provide insights into the stack's limitations, possibilities, and my own understanding, necessitating adjustments to priorities and potentially redefining the definition of done.

No matter how detailed the planning, how experienced I am, or how familiar I am with the stack, surprises are inevitable. It is crucial to be agile and adapt to these surprises. One such surprise occurred just as I was launching the new site, and I will discuss it in a future article.

Conclusion

This is the process I follow when deciding what is necessary for a project. It is a process that I have found effective in navigating the challenges of project planning and execution. By breaking down ideas, setting priorities, and defining success, I can make informed decisions and achieve my goals.